Four men in the British Library

I spent a wonderful day yesterday in the company of four men at the British Library. They said very little, but I learnt so much from them and their work. They are illuminators from fourteenth-century London: talented, funny, inventive and disciplined, and each one had his own particular take on life.

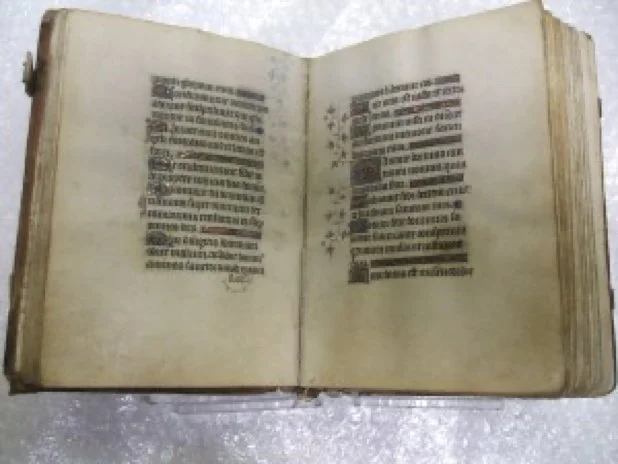

We met in the British Library Manuscripts room where I was given a small box. Inside was a book, no bigger than a paperback novel, but fat, and bound in leather: the Neville of Hornby Hours, made in London in about 1340 for Isabel de Byron, wife of Robert I de Neville. (We’re not allowed to take photos of the manuscripts, but this is a photo of a thirteenth-century book the Ballarat Library kindly allowed me to study.)

We’re not allowed to take photos of the manuscripts, but this is a photo of a thirteenth-century book the Ballarat Library kindly allowed me to study.

The parchment pages crackled softly as I turned them, that lovely rich sound of the old and the well used. The book is nearly seven hundred years old, but the colour is still vivid and strong, glowing: orange, blue, pink, white, black and gold leaf that still shines. Most pages have prayers in Latin, and most have illustrations as well; every page has border decorations: flowers, leaves, vines that wind their way around the block of text, here and there a monster of some kind, usually a hybrid mixture of human and animal peering out.

I looked up at the ‘Issues and Return’ counter; could I really just turn the pages like this, just me and the book? Did they really trust me with this small treasure? Yep, apparently they did.

After peering at some of the illuminations I asked for a magnifying glass to see the details, the incredibly fine lines, the curls, dots and cross-hatching; the single line for curve of an eye, or an eyebrow, or a nose; the curl of a flower stem; the delicate shading of a robe or the shadow on a face. The gold leaf shone, raised slightly from the page when used in a capital, or textured with patterned indentations when used as a background.

For most people, fourteenth-century London was tough, disrupted and crowded. The houses were small and squeezed in, the streets were filthy with mud and rubbish, and while the rich lived well, life was hard for ordinary folk. That image is fairly familiar, but London life was also more than that: the magnificent buildings, the poetry and stories, the gold and silver work, the colourful clothes and the illuminated manuscripts make that clear. The life of the imagination thrived as well. The illuminators of the Neville de Hornby Hours, whatever street they lived in, however small their house and workshop, were talented and committed. I decided I should get to know them better.

Neville Hornby Hours, Marginalia

The previous day I had read a book by an art historian, Kathryn Smith, who has investigated all the illustrations and discovered that the book was written by two scribes and painted by four artists, or limners, almost certainly men, though we have no names for them. At first, all the artwork looked the same to me, but slowly, as I peered more closely, guided by Smith’s descriptions, I could see the differences in style and interest. Slowly, as I turned the pages, the men became more real.

[Note: I could not make these images any larger on the page, but if you double click each one, you will see a larger, brighter image.)

Artist One is the most talented and experienced, the one who plans the book with Scribe One; together they organised the sequence of pages, where pictures would be placed, and who would paint which ones. I imagine he’s a busy man, with other projects to organise as well, so he splits his team into two and assigns tasks to each of them. Perhaps he is the master illuminator, with an apprentice or two. He’s probably older, I think, experienced — he must be, to be entrusted with planning such a large and expensive book. His figures are tall and elegant, and the backgrounds of his pictures are exquisite.

Neville Hornby Hours, f 53. Annunciation

Artist Two is also talented, and One decides to give him most of the major illuminations of biblical scenes. He’s not sure how he does it, but Two has a way of telling a story in a single picture, through gesture and expression; his figures have such energy that they look almost like they’re moving. After a while, looking closely at his drawings, I begin to imagine Two is himself energetic, a storyteller at the local tavern, always ready with a joke and a laugh.

Neville Hornby Hours, f 190. Siege of Jerusalem

He likes to paint the big scenes, but he has no time for the fiddly marginal decorations, the bits of frippery, and he rushes to get them done; it’s easy to see where the paint spills over the edges of leaves and flowers. Artist One argues with him about this, especially when he rushes the borders on his work. In the end, decides to give most of the decoration to his young apprentices.

Artist Three has only a year to go before he is qualified. He can paint figures well, though they seem a bit solid and blocky, and he wishes he could develop some of the fluid movement of the two masters. But the strong sense of physical presence in his work allows him to create depth in his illustrations, so that he can use the limited space inside a capital to great effect, creating a sense of the physical space. This man is, I think, a quiet observer, noticing the play of light and shadow on a row of houses, inside a church, or across the features of the human face.

Neville Hornby Hours, f91v.

Christ and the Doctors

Artist Four is a few years into his seven year apprenticeship, keen to learn, careful and precise, and his border decoration is beautiful. He has trouble, though, with painting figures, so he is given only a few of the larger illustrations.

Neville Hornby Hours, f 133. Judas

He uses only pale colours, not the bright oranges and blues of his colleagues, and I wonder if that is his choice, or a restriction because of his lack of expertise. It’s intriguing that for someone with such an eye for detail, the hands on all his figures are too large, without shape or movement. But I imagine he works hard, frustrated that he can’t quite put down in paint what he sees in his mind, or in his master’s work.

Neville Hornby Hours, Marginalia

Hours passed in the Manuscripts Room and I was caught into another world — not the world that the illuminations presented, but the world of four men, each alone with parchment and paint, but also interacting with each other on the larger project. It took some time for me to begin to distinguish them, to begin to see them and their characteristics.

There are other, more magnificent and richly decorated manuscripts, but beginning to see the strength and weaknesses of each artist gave me a connection with them I would not otherwise have. My musings about what they were like is imagination only, but imagination based in the beautiful, careful paintings they left behind. I also wondered whether a woman might work among them. My research shows that women worked alongside their husband in his trade, but were not fully recognised for their work — a familiar problem. Perhaps, I thought, I could give such a woman the recognition she always deserved.

All photos above (apart from my own photo of the manuscript book) are downloaded from the British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, Egerton 2781.

ED: The British Library is no longer making all manuscript images available.

I am enormously grateful that the Library enabled me to see at least some of the illuminations ‘in the flesh’.